skip to main |

skip to sidebar

© 2010 Simon Hucko

My photo this week was an image I found as part of my normal routine. It has sort of a "still life" feel to it, although I didn't position anything myself. This is probably my favorite thing about phone photography, the ability to capture an interesting image in the everyday. People see the world around them differently, and I'm always intrigued by these little slices of vision. As I've said all along here, camera phones are just fine for your weekly photo. What matters is the image and the vision behind it, not the gear you use to take it.

My pick this week is "Stifling Love" by slithy-toves:

I really like the juxtaposition of the soft heart-shaped leaves and the barbed wire - great find! I also like the lines here, and the way the one vine cuts across the wires. Very interesting and thought-provoking photo, thanks Stacey!

This week's theme will be "change." For those of you in northern climates, Fall is definitely on its way in, and leaves are starting to give up their green and show their true colors, so to speak. Don't feel limited to leaves, though, there are a lot of different ways to express "change" in a photo. Happy hunting!

~S

[title of blog] on flickr

© 2009 Simon Hucko

Pop quiz time. Hope you all play along...

Where's your camera? You should know this without having to think about it, and ideally it should be close by. Go grab it, I'll wait.

Got your camera? Ok, without looking at it, turn it on. (We're going to do a lot of this "without looking" stuff, no cheating!) Before you look, what are the camera settings right now? (Shooting mode, focus mode, set aperture/ISO/shutter speed, image size and quality, etc.) Check to see how you did - at this point the camera should be on and at the settings you thought it was at.

Now to play a bit. Put the camera in an appropriate shooting mode for where you are right now (you can look for this one). Bring the camera up to your eye, frame an image, and fire off a shot. Now, without taking your eye away from the viewfinder, increase the exposure by 2 stops however you want and take another photo. Bring the exposure back to normal and adjust the ISO down a stop (if you're at the lowest setting, put it up a stop), take another photo. Zoom your lens to its widest setting, then all the way to the telephoto end. (Prime? attaboy.) Set the white balance to fluorescent. Switch to manual focus, find a new subject, focus on it and take a photo. Turn the flash on, take a shot. Change the flash exposure compensation down one stop, take another shot. Bring up one of the images on your review screen. View the histogram for that image. Change it so that it displays blown highlights (blinkies). Find the EXIF data and see what shutter speed the photo was taken at. Delete the image. Format your card (only if you don't have anything valuable on there!) Bring your camera back to its normal settings, shut it off, and put it away.

How did it go? Could you do everything without hunting for the controls? Even if you have to menu dive for some things, do you know how to quickly access those menus and make the necessary changes? If you can't easily make these adjustments while shooting, you need to spend more time with your camera. There's nothing worse than missing "the shot" because you were fiddling around with the gear. Spend an hour or two some day walking around your house shooting, adjusting these things as you go. If you have to hunt for a setting, spend some time changing it back and forth to commit it to memory. The less you have to look at your camera, the better.

So how about it? I'm interested to hear how you did. I'll be honest, I had to glance down at my camera for ISO and white balance. Something for me to work on.

~S

[title of blog] on flickr

© 2010 Simon Hucko

I'll admit, I cheated again. I already had this shot in the can when I picked the theme for the week, complete with all it's delicious flare. Last Monday was an awesome evening weather-wise. We had bands of showers rolling through, and the sun kept poking out in between, leading to many a double-rainbow around town. More importantly, when the sun started going down, we had the most beautiful golden hour light I've ever seen. This shot was a bit of a grab shot on the way back to the car - I saw the couple standing by the lake back-lit by the sun and thought it would make a nice image. Luckily for me she leaned in to him right as I picked up my camera, allowing me to capture this great moment. I fired off a few frames, dropped my bag back in the car, and turned around to get their e-mail to send them a shot but they were already gone. Life waits for no one, I suppose... Sure, it has a trendy "engagement session" feel to it, but it totally does the evening justice light-wise.

My pick this week is "Gauangelloch" by djhucko:

© Dan Hucko

No flare here, but a beautiful sunrise capture. I like the framing he chose, putting the fog line on the lower third instead of the visible horizon. This puts the rising sun right at the classical "rule of thirds" placement for the subject, and it gets balanced out nicely by the tree in the lower right. I think this would make a very nice print, too. Excellent capture.

This week's theme is Camera Phone shots. The beautiful thing about your camera phone is that it's always with you. Find a little slice of your world to share with us this week, giving some insight into how you see things around you. Don't worry about resolution or fancy camera apps, a straight up camera phone shot is fine (and you can always pull it into your photo software and tweak it a bit there.) Looking forward to seeing what you guys post!

~S

[title of blog] on flickr

© 2010 Simon Hucko

Practice makes perfect, and photography is no exception to that rule. One of the best things about the digital photography era is the ability to shoot a nearly unlimited number of photos without worrying about additional cost. Now anyone can burn through 100+ frames experimenting with lighting or a new technique or a different subject, whereas the expense associated with such an exercise 10 years ago limited things like that to film school and driven amateurs with a large slush fund. Not only can you shoot as much as you want, there's no delay between pressing the shutter and seeing the image. No waiting to finish off the roll and sending it off for processing (or spending a few hours in the darkroom yourself developing and printing) to find out that you missed the focus or exposure on an otherwise great shot. This, along with the ease of sharing and getting feedback on your work, makes digital photography an incredible learning tool.

It also makes you sloppy.

It doesn't matter if you get it right the first time. Or the second. Or even the tenth. Just keep plugging away until you get something good enough to rescue in your software editing package of choice. Who cares, it's all free, right? Not exactly. What about the time you spend taking multiple photos of one thing until you get it right? How about the time spent in post processing fixing stuff that you could have gotten in camera. And then there's storage, if you're one of those digital pack rats who can't delete a photo you're going to be snapping up hard drives and bogging down your computer with giant photo libraries.

But there's another hidden cost in there - you stop learning your craft. Why spend time on making the perfect exposure when you can correct for it with a slider in post? If you miss on composition a little you can always crop down on the image. (Hey, 12 million pixels have got to be good for something, right?) Horizon a little crooked? No biggie, just straighten it as you go. And sure, these are just little fixes that take almost no time at your computer, but they add up (especially when you're doing them for those 327 frames you snapped on burst mode). On top of that, you're losing resolution and image quality along the way. It's nice to have these tools available, but you shouldn't be relying on them for every shot.

I think this is why so many photographers who started on digital are "discovering" film (myself included). Suddenly every shutter press costs something (from a few cents to a few dollars depending on the film, format and processing). There's no image review with histogram on the back of the camera, so you have to get exposure right the first time. If you take a shot and then walk a few feet and discover a better angle, you've wasted that first shot. You're stuck with whatever ISO film you have loaded in your camera, so you have to make sure you bring the right stuff for the type of shooting you'll be doing. Every film has its own look, too (especially color film), so that needs to be factored in to your final result. The net effect of this is that shooting film is much more patient and deliberate than shooting digital. That clunk of the shutter is like an emphatic period at the end of a long sentence: film choice, composition, lighting, metering, aperture and shutter speed, focus, timing, shutter. Unless your budget allows for unlimited shots, you'll quickly become more selective about what and how you shoot.

What's my point? If you've never done so, shoot some film. Find an old 35mm film camera on ebay or craigslist for cheap (bonus points if it's all manual) with a 50mm lens. Buy a roll or two of film from somewhere that still carries it (CVS around here happens to have a surprisingly decent supply and they still process in-house). Find a way to meter if your camera doesn't - you can use your DSLR for this, or even sunny 16 (ie the force), and make every single one of those 24/36 frames count. Get some 4x6 proofs printed and see how you did. Scan them and share them here or on Flickr. I bet you'll be back for more. Not only that, but it will change the way you look at digital photography - you will simultaneously be incredibly grateful for the ease and speed, and learn to slow down a little and make your images count more.

Note: Getting addicted to film is a dangerous game. You start with a bargain 35mm camera, and before you know it you're processing large format sheet film in your makeshift darkroom in the basement. Don't say I didn't warn you...

~S

[title of blog] on flickr

© 2010 Simon Hucko

My photo this week is a little experiment that I did with some dry ice. It's not a very interesting photo, more of a proof of concept, and I was hoping for something better to share for the week but it didn't work out that way. There are a lot of photos of dry ice on Flickr (mostly as a bubbly smoky liquid in a glass of some sort), but I wanted a different effect. I figured if a long exposure can be used to smooth out moving water, it should have a similar effect on dry ice fog. And it did. 4 second exposure lit by my trusty LED flashlight, which I think is getting close to deserving its own post. Maybe I'll do a "what's in your bag?" thing sometime soon.

This week's pick is "Big Skies over Mendon" by maryshelby:

© Mary Shelby

Big skies indeed. The wide angle really helps capture the big fluffy clouds and gives the photo a nice sense of depth. I like the little red bush (?) in the foreground, too, it adds a nice layer of interest to the photo.

This week's theme is "flare" - point your camera at a light source and let it go wild. An open aperture will give you large blobs of flare across your photo, stopping down reduces these and gives you a starburst effect around the light source(s). Try both and see what you like best.

~S

[title of blog] on flickr

© 2010 Simon Hucko

I've mentioned aspect ratio in passing several times here, but I thought I'd dedicate a post to it, especially since it's something I've been working on lately.

The aspect ratio of an image is the proportion of the photo's dimensions (ie how wide it is compared with how tall). Common aspect ratios for photography are 3:2 (4x6 prints), 4:3, 5:4 (8x10 prints), 1:1 (square), and increasingly 16:9 (widescreen HD). Technically you can crop a digital image to any aspect ratio that you want, but it's much easier to print or display your photos if you stick to the normal formats.

So why so many formats? Why don't we all shoot the same thing? It would make printing and photo site design much easier, as you wouldn't have to worry about differently sized photos popping up. There are two answers to this question, a technical one and a creative one.

The technical answer has to do with legacy film formats. 35mm film has a 3:2 aspect ratio, which is why most DSLR cameras are 3:2 as well. Common medium format aspect ratios were 6x4.5 (4:3), 6x6, 6x7 and 6x9. Large format (sheet film) comes in 4x5, 5x7, 8x10, and 11x14. I'm assuming this is where those standard print sizes stem from, as 35mm never really translates well to any of them... 4:3 and 16:9 are also display formats (normal and wide screen TV), so they make sense for digital photo viewing as well. (I'm guessing this is why just about every point n shoot camera is 4:3.)

The creative reason (which may have driven the technical development mentioned above) is that every format has a slightly different feel to it. Square format photos have a very static well defined feel to them. As you deviate from square, photos start to feel wider or taller, imparting somewhat of a dynamic feel even before considering the subject. As an example, I took to photos of essentially the same subject last weekend. The first is a square shot -

© 2010 Simon Hucko

Despite the movement in the water it's a pretty static and calm shot. Compare that with the same scene framed in 2:1 -

© 2010 Simon Hucko - click to see it large

Note that the vertical captured is about the same for the two (from just above the bridge to the bottom of the second little waterfall). This time, however, we're capturing a larger part of the scene. The bridge goes from being a static and self contained subject to part of a sweeping image. (Note also that I bucked those formats I talked about and went with 2:1. If I were to print this at some point I'd have to get it printed in a less wide format like 3:2 and trim it down, then custom mat and frame it. A bit of work, but worth it for wider stuff like this.)

So how do you decide what format to use? Well, that's up to you. As I already mentioned, more square formats tend to feel more static and complete, where wider (or taller) formats can give the feeling of movement. Sometimes the subject dictates what format to use, where the interesting compositional elements are contained in a certain layout and you crop out the rest. Sometimes you have more freedom to choose a format, in which case it's worth experimenting with a few options and seeing what you like.

Often times when I approach a subject I'll have some idea of what I want the final format to be. Certain scenes just look square to me, and certain ones benefit from a bit of extra width. I then compose my shot with the crop in mind, making sure I fit all the elements into the space that I'll wind up using.

If you approach a scene and aren't sure what format you want, my advice is to compose a little loosely so that you'll have more options while editing. Make sure all of the key elements of a scene are in your photo, and then back up or zoom out a little to leave yourself a cushion for cropping. There's nothing worse than going for a square crop and coming up just short of including the entire subject (trust me, I've been there, and 4x5 just isn't the same...)

The right crop can elevate a good photo to greatness. So much of photography is eliminating objects from the frame and only including the ones that add to your story. I strongly suggest familiarizing yourself with the effects of different aspect ratios on your photography. If you have a photo with a good subject that still feels a little unfocused to you, try cropping out different parts of the image and see if you can increase its impact.

I've been getting more and more into square format lately, as a stroll through my photostream will quickly show. I still shoot a lot in 3:2 (the native ratio for my camera) since that's what I compose in. I also like the super wide 16:9 (or 2:1) for certain scenes. I've been on the lookout for vertical 1:2 images as well, but those are hard to come by (if you want a challenge, spend a day shooting for that crop).

What's your favorite aspect ratio?

~S

[title of blog] on flickr

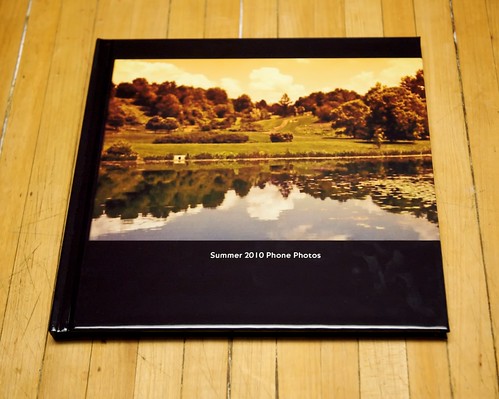

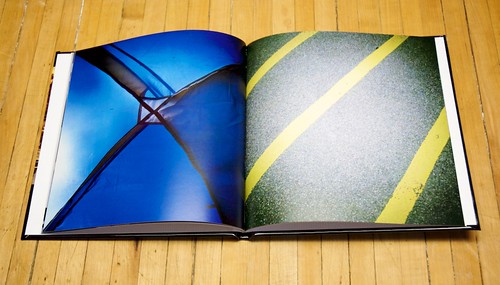

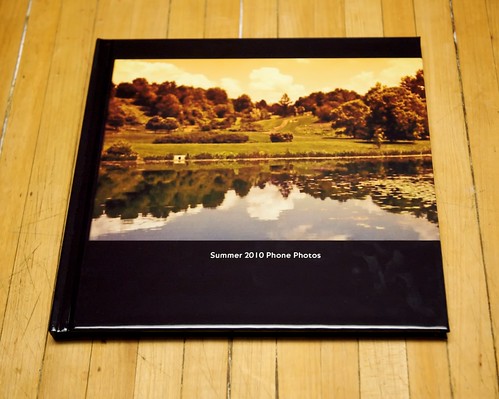

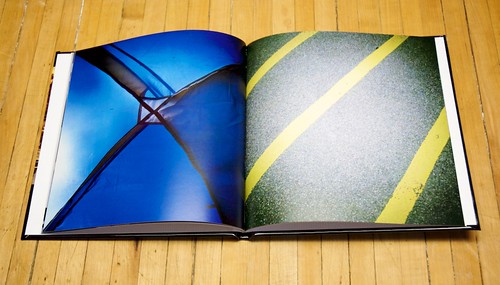

A quick plug for Shutterfly. If you're not a member, I encourage you to go sign up for an account. I believe you get something like 50 4x6" prints just for joining.

The reason that I'm mentioning it here is that they have sales on their photobooks every few months. Occasionally, they'll even give one away for free. They were running a free book promotion at the end of the summer, so I threw together a small collection of phone photos and had it printed up for less than $9 after tax and shipping. Their print quality isn't great by any means, but it's plenty good enough for personal stuff. My wife and I have replaced doing photo albums with ordering these books: every time a sale comes around we'll pull photos from recent events and order one. Sure, it's probably cheaper to keep albums of 4x6 prints, but the space saving and convenience is worth the extra cost (and in the long run I think that extra cost is very minimal once you consider album and print cost and the time it takes to put all the photos in the sleeves). It's nice to be able to design layouts and add text, too, although I went for full bleed with these photos to be artsy (or something like that).

If you've never printed a photo book, I suggest giving it a try. It's pretty cool to get a hard copy of your work that you can pass around to friends and family.

Note: I'm not affiliated with Shutterfly in any way, other than being a customer. I'm certainly not making any money off of this post.

~S

[title of blog] on flickr

© 2010 Simon Hucko

So "square" as a theme is almost cheating for me: I'd say a good third of my work these days ends up as a square crop. I probably could have stretched myself a bit to find a square subject, but I didn't have any time to shoot this weekend so I had to go with something from earlier in the week. This spot is at the end of a small lake downstream from the local reservoir and is apparently quite a popular swimming hole. There were some kids jumping off a cliff, and then this group that swam over to the dam. I was on the cliff above them and grabbed the shot. There was actually a fourth swimmer in the frame behind these three, but I cropped him out when going to square (3 subjects is much more visually pleasing than 4).

My pick this week is "River Severn - Ironbridge" by q-pix

© q-pix

Lovely black and white landscape. However he did the black and white is very nice, lots of texture and detail across the image. Nice use of the river as a leading line to bring the viewers into the frame, too.

This week's challenge is to use the widest angle lens you've got and make a compelling photo with it (no cropping allowed!). Don't just default to a wide landscape, either, there are a lot of interesting things you can do with a wide angle perspective (people, places, objects, the sky's the limit!). Flip your landscape to vertical and capture an interesting detail in the foreground. Give some great context to your environmental portraits. Surprise me, or give me something simple but excellent.

I'd also like to see a few people who are hovering around at the fringe come back to the fold and start posting again. We miss you guys! Thanks to the core group who's been keeping up with me here, it's nice to have your photos every week :)

Go shoot!

~S

[title of blog] on flickr

© 2008 Simon Hucko

When talking about photography, the comparison between a camera and the human eye inevitably gets discussed. Lately this discussion usually centers around dynamic range, and getting a scene to look more "natural" through HDR imaging. Sure, we're able to see a lot more detail than our camera sensors, but there's a lot of half-truths and misinformation floating around out there.

Let's start with some basic anatomy (mostly referenced from wikipedia). The human eye is indeed set up somewhat like a camera. We have a lens, an aperture (your pupil, which is actually located in front of the lens), and a sensor (optic disk). The optic disk actually has two types of light sensing receptors, rods and cones. Rods cannot perceive color but are very sensitive to light and give us our low light and peripheral vision. Cones are the color receptors and make up what we think of as our normal vision. Our pupils have an aperture range of roughly f/2-f/8. We have an approximately 170 degree wide by 120 degree vertical field of view (which is huge, like fisheye huge!), but the actual sweet spot of your vision is much smaller (sorry, don't have a number for you). As far as resolution goes, I've seen numbers all over the board. You have about 5 million cones in your eye, so you get 5MP of color resolution. But then you have another 100 million rods that give b/w contrast, which adds another 100MP. On top of that, we have two eyes, and we're able to sweep them around the scene and soak up more detail, so some people estimate our resolution around 500MP or more! But I'm not sure our vision is good enough to actually resolve all this (worse for some than others), and the dynamic aspect of our vision and the crazy processing that goes on in our brain makes resolution somewhat pointless to talk about. Suffice to say that what we resolve and what we actually need to see an image are two different things.

On to the dynamic range can of worms. Your eyes have a static contrast ratio of about 100:1, or about 6 1/2 stops. Seems kinda low, doesn't it? Static contrast ratio means what you're able to see without any adjustments. Add in allowances for pupil dilation and chemical adjustment of your photo receptors (sort of like changing the ISO on your camera) and you get to a dynamic contrast ratio of 1,000,000:1, or about 20 stops. (Note, dynamic contrast is a term often thrown around by TV manufacturers, too, and is a bit of handwaving to get themselves a bigger number. Shop by static contrast ratio whenever possible). So, when scanning around a scene, you're able to see those shadow details and the bright highlights because your eyes are adjusting as you go. Try looking at something bright for a second and then quickly turning to something dark and you'll notice that it takes a bit for you to adjust and fully see what's happening (think driving into a tunnel or walking out into a sunny day from a relatively dark building). Therefore, your camera isn't really doing that bad a job (most digital cameras capture 5-9 stops of light), it just doesn't have the ability to adjust across a scene the way our eyes do.

So what do we do? Bracketing shots for HDR makes sense, because we're doing the same thing our eyes do - adjusting the sensitivity to resolve detail in different parts of the scene. What doesn't make sense is viewing these images at 500p on the web. No wonder HDR looks so fake, we don't actually see all 20 stops of information at once normally. For HDR to work, I think you'd have to view it at a large enough size that you can't see the whole image at once. Actually, for HDR to truly be effective, we need to replicate the scene in the way that our eyes see it - a large image of around 6 stops of dynamic range that adjusts which 6 stops it shows you based on where your eyes are. Sounds kind of sci-fi, but retina tracking is very real, and I imagine something like this isn't out of the question (although not easy and certainly not something that's going to be built into every display out there). That or we need a display with a bright enough light source and an actual contrast ratio of 20 stops so that our eyes can do what they do best. That might be a more reasonable approach.

HDR aside, there are other things that our eyes and brain do naturally which influence photography and post processing. Let's start with vignetting. Why does a vignette on a photo work? Because our vision is the same way. Take a second to examine your peripheral vision. It's a bit darker, kind of oval shaped, right? So looking at a photo with a bit of vignetting gives us the impression of standing there looking at the scene. (Note that I said a bit of vignetting, you can definitely go overboard here.) You can take it a step farther and slightly desaturate and blur the edges of the photo along with the vignette, giving a much more true-to-life view. This is partially why I love larger format film photos taken with older cameras, they seem to produce this effect naturally and wonderfully.

Black and white works because we have so many more receptors for light and contrast than we do color, so we're visually attuned to that anyway. In fact, when you're stumbling around in a dark room, you're getting very little color information from your eyes. So, even though black and white was initially a chemical and technological limitation, it also relates to how we see the world on some level.

Color temperature and white balance are such a pain because we don't normally think about it. Our brains are incredible at adjusting and adapting to color temperature, and even mixed lighting can look normal and right in our mind. However, if you've ever tried to photograph a room with fluorescent, tungsten and daylight you've probably gone insane trying to balance them all out. I'm not sure why our brains don't balance this information in an image like they do with real life, possibly an image on a screen or wall is lacking the context that we get in real life and the references for color as they pass through different lighting. The important thing here is to learn to see these color differences before pressing the shutter so that you can adjust for them (gels, custom white balance, turning off the fluorescents all together, etc).

Finally, your brain is an incredible processing engine, and it constantly lies to you. There's a difference between what your eyes see and what your brain sees - a lot of things get processed out and ignored (because if the 500MP guys are right, that's just way too much information to handle on a constant streaming basis). You're physically attuned to filter out distractions and familiar objects, focusing on what's changing or where your interest lies. This filter never shuts off, so when you're composing a shot through your viewfinder it's easy to overlook things like branches, telephone wires, and other distractions that will later become glaringly obvious in the photo. With some practice it's possible to turn this filter off and really see what's there in front of you, which will help greatly in processing. (Let's face it, cloning stuff out that you could have fixed on site sucks.) This is also why some images just don't come out as strongly as you hoped - all of the context that you had when you were there and taking the photo doesn't get represented in the image, just whatever was in the frame. It's up to you to take that frame and place it around the important elements of a scene, capturing what you feel in a small 2D slice of time. Sometimes that's not even possible, and recognizing what won't work as a photo is part of the battle. Hey, no one ever said photography was easy.

I hope this was somewhat informative and that it gives some insight into why your eyes and your camera see the world differently. Spending a few minutes thinking about the difference can save you from a lot of trial and error with your camera. And please, for the love of god, no more sloppy, tiny, halo ridden, gray HDR - there's nothing natural about it.

Note: most of the information in this article comes from wikipedia, other random googling, and my own reasoning and experiences. If I missed something or got something wrong, please let me know in the comments and I'll correct it.

~S

[title of blog] on flickr

Huge thanks to Matt Beaty for picking me for the comment of the month contest he's running on his blog (Vault Photography Blog).

Matt is working his way through photo school at Northern Arizona University, and talks a lot on his blog about his experience as a photo student, along with his other photographic endeavors. He takes some excellent portraits, and shares his experiments on the blog (including what didn't work, which can be more worthwhile than what did sometimes). I enjoy his somewhat irreverent view on photo school and photography in general, and always like seeing a new post pop up in the reader. Please head over and give it a read, and consider adding it to your RSS reader too.

Matt also asked me to write a guest post for him some time, and I'm hoping he'll trade with me one week so that I can host him here.

You can find Matt in the following places:

Vault Photography Blog

Twitter (give him a follow)

Flickr

Vault Photography

~S [title of blog] on flickr

![[title of blog]](http://1.bp.blogspot.com/_dADuhpc-QVg/TJkTQCq15KI/AAAAAAAAKtQ/usbfWPD7pjc/S1600-R/waterfall.png)